The University of Florida has pioneered a method that uses artificial intelligence to find a disease early so growers who produce summer squash can keep it under control. Early detection gives farmers a fighting chance at a better crop.

Summer and winter squash are grown commercially throughout the US state, particularly in southeast and southwest Florida. In 2019, Florida growers harvested 7,700 acres of squash, with a production value of US$35.4 million, according to the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. But powdery mildew disease, common throughout the world, can decrease yields.

For the study, UF/IFAS researchers used a sensing system attached to drones to collect spectral data of powdery mildew on summer squash in the fields and labs of the UF/IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center.

First, the researchers worked to identify the best spectral wavelengths for early powdery mildew detection — on leaves that either had no symptoms or exhibited early symptoms.

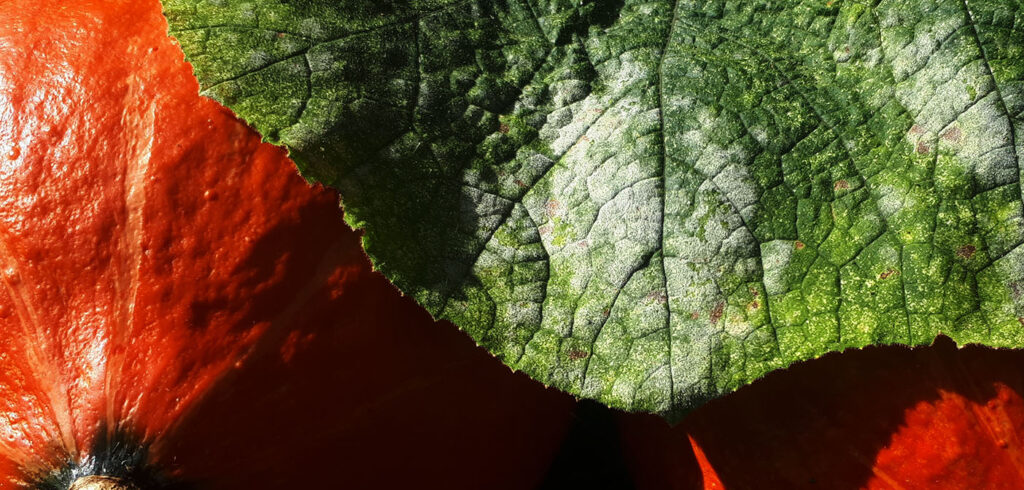

The main symptoms of powdery mildew are white spots or patches on a squash plant’s leaves. Diagnosing powdery mildew in early infection stages is difficult because more mature leaves are usually susceptible to the disease first (due to poor health) but are often obscured by other leaves. When a more prominent upper leaf begins to display the familiar white spots of mildew it is much harder to stop the spread of the disease.

“In short, a disease could change the leaf properties and affect the amount of light being reflected from leaves in areas outside of the visible spectrum, which humans cannot see,” explained Yiannis Ampatzidis, a UF/IFAS assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering and co-author of a new study recently published in Biosystems Engineering.

UF/IFAS researchers then used machine learning — a subset of artificial intelligence — that can ‘learn’ from spectral data to detect powdery mildew. The trained machine-learning model is able to identify powdery mildew in different disease development stages. It is capable of building a mathematical model to detect powdery mildew without being programmed by a human to follow specific steps.

With the images and spectral reflectance analysis of squash leaves, scientists detected powdery mildew about 95% of the time. In fact, even without visible symptoms of the disease, the technology showed researchers the disease 82% to 89% of the time.

“The ideal environment for powdery mildew to infect is humid weather, high-density planting and shade,” explained Ampatzidis. “It is crucial to identify powdery mildew early, since the disease spreads rapidly and the lesions increase in size, developing a dusty white or grey coating,” he continued.

“Early detection of any health problem, whether in humans or plants, gives the best chance of controlling it through early intervention,” added Pamela Roberts, a UF/IFAS plant pathology professor. “Likewise, plant diseases are more easily controlled early when the pathogen population is low, compared to later in the epidemic.”

“Additionally, this technology may actually decrease the use of chemical sprays, by eliminating applications that could be made before there is actually any disease to control,” continued Roberts.

“Since powdery mildew is a chronic problem on squash in southwest Florida, it is only a question of when, not if, the disease will appear. Accurate timing of fungicides, whether in conventional or organic farming, can increase the efficacy of the product and decrease losses.”