For African countries like Kenya and Somalia, 2020 has brought some of the worst locust outbreaks in over fifty years. This is a story repeated in South West Asia with both Pakistan and India reporting the most severe plagues in decades. Climate change and extreme weather events are thought to be behind the sudden rise in locust numbers with hot and humid conditions favouring breeding over the past two years.

It is estimated that an average desert locust swarm eats the same amount of food in one day as approximately 2,500 humans. Food crops are being decimated affecting the livelihoods of poorer farmers and increasing the risks of starvation in already vulnerable regions. Tackling locust infestations and controlling swarms is not easy, but it’s being aided by modern technology in the form of supercomputers and drones.

Supercomputers: predicting the birth and movement of locust swarms

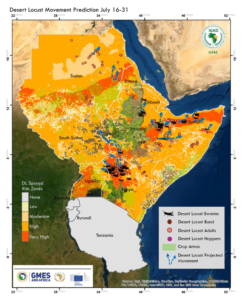

Locust swarms can travel up to 100 miles/150 km per day making their paths difficult to monitor from the ground. A UK-funded supercomputer built in Kenya (at the regional climate centre in Nairobi) uses satellite data to track locust swarms. The latest projection for example reports that ‘crop destruction continues to be reported in Ethiopia and Somalia. Most affected crops have been sorghum and maize crops at vegetative and ripening stages.’

This new locust tracking technology also produces extensive weather forecasts to predict the high winds, rainfall, and humidity that provide ideal breeding conditions for locusts so climate experts can predict their next destination.

“Through UK aid and British expertise, we are helping to track, stop and kill dangerous swarms of locust to help millions of people fighting for survival” said UK International Development Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan on the projects’s announcement adding “With rising temperatures and increasing cyclones driving these infestations, Britain is stepping up to help vulnerable communities prepare for and adapt to the catastrophic impacts of climate change.”

The supercomputer has been provided through the Department for International Development’s Weather and Climate Information Services for Africa (WISER) programme, in collaboration with the Met Office and the Africa Climate Policy Centre.

The UK has also provided £5 million to an emergency UN appeal to help vulnerable communities in Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Tanzania so that they may use this new supercomputer data to prepare for the arrival of locust swarms. This support will fund surveillance of the locusts and the spraying of aerial pesticides to kill the insects, protecting 200,000 acres / 78,000 hectares of land.

Drones: Tracking and spraying locust swarms in the fields

Drones can also play a key role in monitoring locust swarms and their potential feeding grounds with fixed wing drones ideal for surveillance and green pasture spotting. Rotary wing drones can hover in place to take photographs or be fitted with sprayers to treat swarms with pesticides.

However, the range of the average rotary drone is quite limited as is its ability to carry large pay loads of pesticides/chemicals, specialised spraying drones are needed. Drone propellers have also been found to be susceptible to damage if they find themselves caught within a dense cloud of flying locusts.

The positives of drone technology are outweighing the negatives for now though and in India the Ministry of Civil Aviation issued an order earlier in 2020 granting ‘conditional exemption’ for the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer Welfare to carry out their anti-locust operations using drones. They have joined the ground vehicles and helicopters spraying pesticides onto swarms.

There are reportedly fifteen drones deployed in the area of Rajasthan to spray pesticides on tall trees and in otherwise inaccessible areas. Other affected Indian regions embracing the versatility of drones include Punjab and even parts of Madhya Pradesh. These drones are surely more effective that the more traditional locust protection methods employed by Indian farmers – beating “thalis” (plates) to make a lot of noise (although they still do that too).

Across the border in Pakistan drones are also now joining the fight against the desert locusts. Twelve specially designed T16 high-tech farm drones from Chinese Drone manufacturer DJI have been donated by China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. A single T16 drone can spray insecticides over 25 acres / 10 hectares of farmland every hour – much more than standard rotary drones. An operator can even control five drones at the same time without actually being on the field.

There are of course always health and sustainability concerns about pesticide use, one interesting organic locust control project that came out of Pakistan’s recent plague saw members of the public paid to collect locusts at night (when they are dormant and easily caught). They were paid 20 rupees (12 cents) per kg and it was so successful that the project quickly ran out of budget. The harvested locusts went to a company called Hi-Tech Feeds – Pakistan’s largest animal-feed producer – which replaced 10 percent of the soybean in its chicken food with the insects. Insects in animal feed are something of a growing trend.

With predictions that, like COVID19, there could be an even bigger second wave, all the countries between East Africa, the Middle East and South West Asia are on high alert. If climate change causes locust plagues to become the ‘new normal’ we will certainly need technology and more to help in the fight to control swarms and protect the ever precious world food supply.