In June 2019, the UK became the first major world economy to set a target for achieving net zero on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into law, with then Prime Minister Theresa May committing the UK to net zero emissions by 2050.

Emissions from UK farms amount to about 10% of UK GHG emissions but only a tenth of this is carbon dioxide; more than half of agricultural GHG emissions are methane (CH4) and nearly 40% are nitrous oxide (N2O). Reducing these emissions is more difficult than cutting carbon dioxide, because they result from complex natural soil and animal microbial processes, suggests the National Farmers Union.

Beef and dairy production has received considerable attention from lobbyists, who suggest that since cattle are significant producers of methane from flatulence and manure, reducing the amount of meat and milk consumed will help to address the issue. Research is also ongoing into modifying or supplementing cattle diets to reduce methane production.

However, farmers are already active in making use of manures for renewable energy production or to replace mineral fertiliser.

Cutting energy costs on farms with anaerobic digesters and biogas

The concept of using slurry for bioenergy production is nothing new, but it is usually just a minor constituent in feedstocks which also include higher energy sources such as maize, grass or food waste.

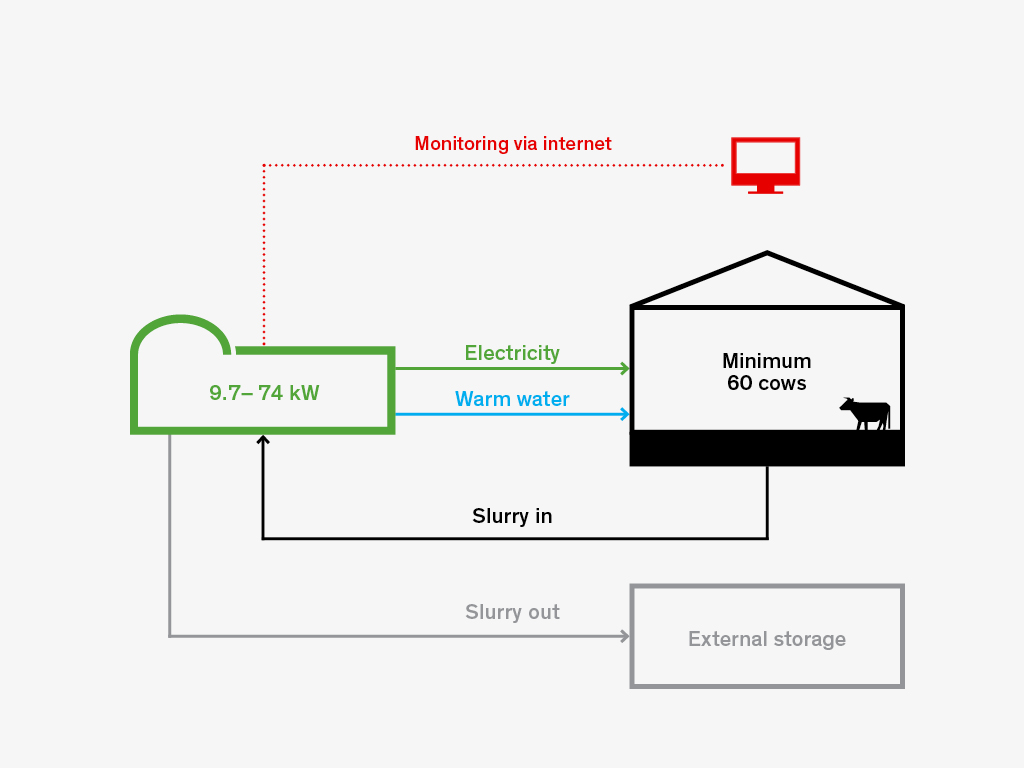

Belgian manufacturer Biolectric’s ‘micro’ anaerobic digesters are now being installed by individual dairy farms with slurry as their sole feedstock to produce electricity and hot water for the farm’s use.

Gary Hague of UK importer Dairy Energy explains: “Farms have slurry readily available as a waste product to dispose of, and while it doesn’t have a high energy content, it offers an opportunity to offset the cost of the farm’s electricity, and could cut its carbon footprint by 30%.”

Best suited to farming regimes where the cattle are housed for much of the year, slurry is pumped from the farm’s reception pit into the anaerobic digester, which breaks down the organic matter to produce biogas, used as a fuel in combined heat and power (CHP) engines to generate renewable energy. Once installed the system is said to require just 15 minutes per day for maintenance and programming. The average size is 33kw output, which matches well to a 200 cow herd, points out Mr Hague, and its two CHP engines produce flexible amounts of electricity and hot water.

In addition to the power produced, the farm also benefits from digestate, in which nutrients are more readily available to crops than in slurry, cutting fertiliser costs.

“It’s a system that works well for dairy farms with robotic milking systems which have a high power requirement 24/7; these farmers are also used to programming and monitoring equipment,” comments Mr Hague.

The units fit neatly into existing farm layouts, he suggests, with a 33kw digester at just 14m diameter.

Where the digester produces hot water – which could also be utilised by the farmhouse – funding may be available under the Renewable Heat Initiative (RHI) which runs until 2021; after this the removal of other subsidies means that farm biodigester schemes could be eligible for other agricultural funding.

“Just by offsetting the electricity costs which can be £40,000-£50,000 a year, installing a Bioelectric system can pay for itself in 4-7 years,” comments Mr Hague.

Court Farm is a family run business located on the Gloucestershire/Herefordshire border in England, milking 260 Holsteins via four Lely astronaut robots, and has installed a 33kW digester.

Richard Carter, son-in-law of Mr & Mrs C Pugh who own the farm, says: “We saw it as a good add-on to our business to use our slurry to produce electricity and heat.”

“It has reduced our £35,000 electric bill by 80% so far. We are also going to receive a feed-in tariff and RHI, plus there are some hidden benefits as the digestate has a higher fertiliser value which in turn will reduce our bought-in fertiliser costs… we also feel it will put us in a better place for any future environmental legislation.”

He adds: “With electricity rising at an alarming rate the electricity and heat savings will save us in excess of £50,000 per annum. The hot water produced will provide heating in the farmhouse and our farm cafe along with hot water for the robots and washdown offering additional savings”.

Biogas tractors – reducing ‘well to wheel’ greenhouse gas emissions

Machinery manufacturers are considering alternative fuels to meet future environmental legislation which has already resulted in continued updates to engines to cut emissions.

New Holland’ s 179hp T6.180 tractor is capable of running on methane, CNG or LNG, and powered by an engine derived from sister company Fiat Powertrain (FPT)’s unit proven with alternative fuels in the Iveco Eurocargo trucks since 2004.

Methane fuel can be supplied by an AD plant, using biogas that has been upgraded and compressed, and New Holland is exploring the concept of the ‘energy independent farm’ with customers who produce manure or biomass as feedstocks for biodigesters or have such facilities on their doorstep.

This scenario would offer the greatest benefits in reducing ‘well to wheel’ greenhouse gas emissions.

“Using biomethane produced from liquid manure cuts emissions by 180% and takes the operation into negative C02 as the process captures gas that would otherwise have been released into the atmosphere,” explains Mark Howell, Global Head of Renewables for New Holland.

Opportunities could also be offered for a small group of farms working together to produce gas which is exported to a central injection point, fuelling two or three tractors on each farm.

Using CNG/LNG from the grid would also reduce the carbon content, but requires the use of proprietary kit to compress the gas to 200bar.

“This is a common method of fuelling in Europe and has been successfully used in the public transport sector in the UK. In addition to the environmental benefits, the cost savings can be impressive, up to 80%.”

The obvious way to make use of a gas-powered tractor is in yard work such as feeding livestock, where it is running for a set period each day and the tank is refilled overnight, although quicker fills can also be made for field work such as haulage, where the tractor can frequently return to the yard to top up. Applications including airport de-icing and hedge cutting are also being explored.

Purchase cost of the T6.180 comes at a 15-20% premium over the diesel version, but with savings of £8000/year have been calculated for a tractor putting in 3000 hours a year.

Nitrogen fertiliser from biogas digestate

Norwegian company N2 Applied has developed a technology to produce nitrogen fertiliser on the farm, from manure or biogas digestate.

The nitrogen content of manure alone is too low for a balanced fertilisation for most crops, with further loss of ammonia (NH3) during storage and application.

Treating manure with a mix of nitrates (NO³) and nitrites (NO²) during storage and before application converts the ammonia to a stable fertiliser with high nitrogen content. This can more than double the effective nitrogen content of the manure, says N2 Applied.

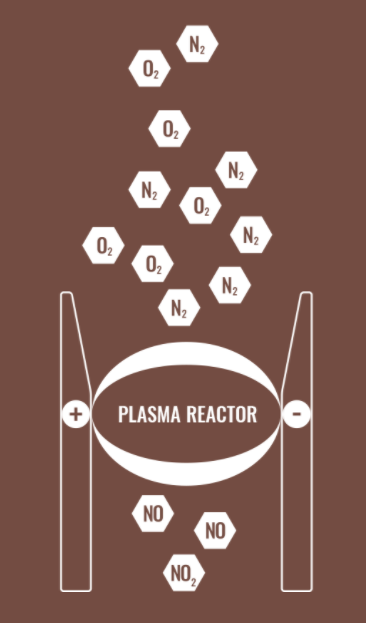

The N2 plasma reactor fixes nitrogen from air by splitting the N2 and O2 molecules in air into N and O atoms forming nitrogen oxides. The nitrogen oxides are absorbed into liquid manure or biogas digestate and combined with free ammonia to form ammonia-N.

All N2 plasma reactors are connected to N2 Cloud where production data is stored and analysed, enabling remote operation and maintenance of the reactor.

UK business development director Chris Puttick explains: “We are releasing a small number of units into the market this year with innovative early adopters and strategic partners. At the same time we are further evidencing the yield enhancement from plasma treatment and significant emission reductions with independent research groups across Europe and the UK.”

Northern Ireland dairy enterprise Bingham Farm has installed the N2 Applied system with the support of AFBI and has established trial plots to show the yield benefits of treated digestate. The 750-cow herd is zero grazed with manure fed into the farm’s biodigester and Mr Bingham says: “The system has reduced ammonia emissions and cut odours in a region which is heavily populated with livestock so we are more environmentally friendly; it has also cut my reliance on chemical fertiliser, keeping our nutrients on the farm.”