Picking asparagus spears is hard, back-breaking work – so why not let a robot do it?

The UK agricultural sector was already primed for a new approach to fruit and vegetable harvesting as it approached Brexit, with the inevitable labour shortages expected to follow, and then Covid-19 hit, further straining the available pool of workers.

Recruiting asparagus pickers has proven particularly challenging, given the precise nature of the task where spears have to be individually selected and cut just below the soil, as well as the enormous quantities that have to be gathered in a short season lasting just two to three months.

Some crops were reportedly left to rot earlier this spring due to a failure to secure workers, while those farmers that were more successful faced a large bill, attributing some two thirds of their costs to labour.

“We’re approaching a big labour shortage in the UK,” notes David Sands, the founder of ST Robotics, a Cambridge-based firm (UK) currently working with a large, local producer to perfect a robot to pick asparagus. “All the paperwork required after Brexit for Europeans to come over here for just two or three months’ work will mean either costs go up or there will be a shortage – or both. Some farmers are talking about abandoning valuable fields altogether, simply because they can’t find labour.”

Spot the difference

Asparagus lends itself to robotic picking because AI-driven machine vision can easily identify individual spears as there are no leaves to obscure the product: “You don’t have weeds or too much going on around it,” explains Sands. “If you look down on a field of lettuces, it’s just a sea of green – how do you pick it on a commercial scale, if you can’t distinguish one from another?”

Regardless of the individual nature of the crop, all agricultural robots have to be rugged enough to survive the weather, able to navigate uneven terrain, and continue to work despite connectivity issues. “You can’t send your average AGV working inside a factory out into a field – it simply wouldn’t survive,” agrees Sands. “Farm machinery has to be very well built. We also plan to use a central console to first teach the robot, but how do we communicate with it when it is the other side of a two-acre field?”

Previous attempts by other companies to automate the process have failed to impress Sands: “Some robotic harvesters have already been developed but their approach has been from the perspective of agricultural machinery – not robotics,” he notes. “There’s one that’s dragged behind a tractor, and another that claims it’s robotic but has a guy sitting on it the whole way across the field.”

These earlier efforts work more like farm machinery – cutting the asparagus while moving, and using rotating grabbers to pick it, resulting in some spears being missed or damaged. “White asparagus should really be cut just below soil level, otherwise the exposed stalk left behind is vulnerable to bacteria and weather,” continues Sands.

“That’s what we’re trying to do – to harvest it in the same way as a human being. Our robot will keep stopping – instead of continuously moving, it will come along, stop, look at the ground, identify the spears ready for harvest, pick them, and move on.”

How will the robotic asparagus picker work?

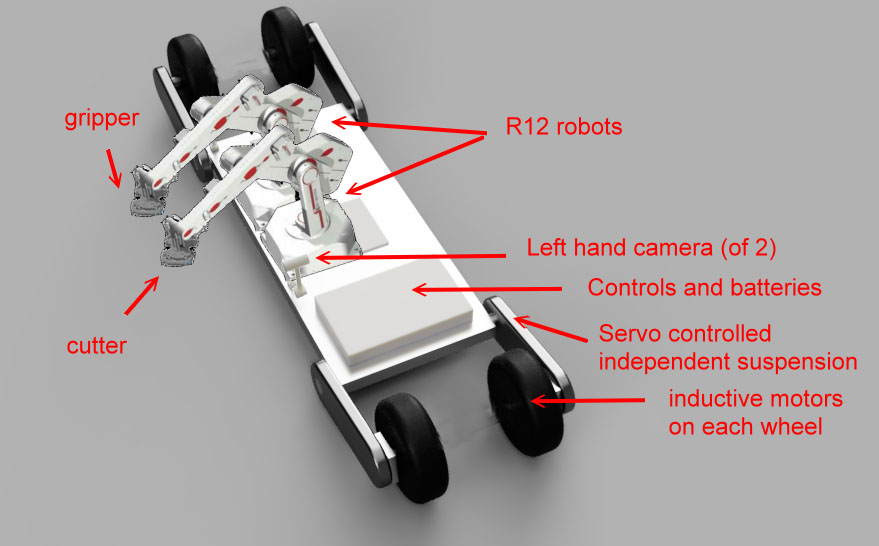

ST Robotics envisages a solution using two of its existing ‘R12’ robotic arms mounted side by side on a vehicle with a long wheelbase close to the ground. The robot will run alongside the asparagus bed (a later version will span three beds), potentially on linear tracks. A vision system will identify spears of the desired size, within reach. One robot arm will then hold the base of the spear while the other cuts the stalk just below the surface, emulating the human process. Once cut, the first robot will gather the spear onto a tray mounted on the vehicle.

However, at this stage, Sands admits there is still a long way to go: “Currently we have a conceptual design – a CAD version, but please remember we have been making robots since 1985.” To begin with, he says ST Robotics will use an operator to see what the robot sees and choose the asparagus to be cut. This will train the AI system to know the difference between a good and a bad spear, so it can work out which to take.

“Basically, there are three conditions,” notes Sands. “First, the spear is adequate – pick it; alternatively, it’s trash, but you still have to pick it, but then discard it; and the third is that it’s not big enough, so you leave it there. With asparagus, you have to deliberately leave some behind above ground, to grow.”

The next step – prototype development and first trials – will hinge on whether the company secures funding from Innovate UK, the UK’s innovation agency. “We’ve applied for a grant, which we should know more about by November,” says Sands. “If we’re successful, we could begin trials next season [March/April 2021], using some raised beds in an indoor environmental chamber.”

It should be noted that asparagus takes up to two to three years to fully mature – fortunately Sands had the foresight to reserve some for use in first trials: “We’ve got some waiting ready for us to take home and plant in our raised beds,” he says. “That’s one of the things that we have to bear in mind with this project – the horticulture has to be considered, as well as the robotics.”

The business case

For farmers, the cost of any new equipment also has to be considered. However, with the asparagus global market expected to be worth US$37 billion by 2027, such revenues should help pay for sophisticated robot technology, with Sands suggesting a return on investment in as little as three to four years.

“We expect to sell the robot at £50,000 per unit, targeting growers of greater than 25,000kg output per annum, where labour fees would be typically £15,000 to £25,000 per season, giving a payback of no more than four years to growers, and even less for larger growers,” he says.

For smaller growers (no more than 25,000kg crop output), ST Robotics plans to hire individual units at £1,500 per month (£4,500 per season). “This would deliver immediate cost savings to labour fees, which would range from approximately £5,000 to £15,000 depending on crop volumes,” states Sands. “We’ve already had overwhelming interest from growers who tell us they need these machines now – otherwise they are going to have to shut fields down or switch to less labour-intensive crops.”